This is a guest article from disability rights lawyer Dr Abigail Pearson.

In October 2023, the full single-use plastic ban came into force in England, three years after plastic straws had been outlawed. This was a confusing day for disability equality in the United Kingdom.

Much has been said about the impact of the restriction of access to plastic straws for people with disabilities by disability organisations and individuals alike.

I’m a disability rights lawyer who relies on straws and plastic to eat and drink (due to swallowing issues, I need pureed food, so baby food pouches are enormously helpful during work travel). What struck me was that nobody had considered the legal disconnect between the aims of the Equality Act and the exemptions in the single use plastic ban.

The problem: the single-use plastic ban threatens disability rights

The single use plastic ban restricts sales of plastic straws to outlets such as pharmacies. It also creates a requirement to declare and justify the need for straws to bar and service staff.

This creates, rather than removes, barriers to equality – and automatically links disability with illness, an image which people with disabilities have worked hard to dispel.

The Equality Act (2010) protects people with disabilities from discrimination because of inaccessible goods and services. It requires providers to take reasonable steps to remove substantial disadvantages and to provide auxiliary aids such as ramps and hearing loops where necessary to overcome these.

Drinking is something that most of us do with little thought throughout our day. Yet, if we were to sit and think about it, we would soon realise how much it adds to our everyday life. From the pleasure of our first sip of coffee to start our day, to the cup of tea that accompanies the chocolate bar to get us over the 4pm slump, to the glass of wine in the evening with dinner.

Then there are the other drinks that are instrumental to more than our well-being: the coffee dates with friends, the work networking drinks, the drinks in celebration of weddings, birthdays, or the beginnings of other new chapters.

Viewed from this lens, drinking moves beyond the purely biological need to stay hydrated to a crucial part of our social, cultural, and economic lives.

If you need a straw to enjoy these drinks safely and you cannot access one, then you are cut off from a variety of important relationships and experiences.

The ecological alternatives to plastic straws, though fashionable, are not always appropriate. Metal and glass can be too hard and cause injuries. Paper can disintegrate in your mouth leading to the choking hazard that a straw is meant to avoid.

The impact of the changes can be seen in the sale of signs and badges explaining the need for straws, suggesting that some were fearful of judgement or intrusive questions.

The Government’s supposed commitment to this social and human rights view of disability was evident in 2009 when the UK government pledged to ensure compatibility with domestic legislation and the aims and scope of the United Nations Convention to the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

This recognises the inherent dignity of people with disabilities and their right to social and political participation in all areas of life. This promise was repeated in the 2021 National Disability Strategy.

The solution: designing ways to access plastic – ‘Placcess’

How might we address this legal inconsistency and societal barrier whilst recognising the importance of environmental preservation, including people with disabilities?

The answer, I suggest, is to start to talk more about ‘Placcess’. Blending the words ‘plastic’ and ‘access’, ‘Placcess’ allows us to consider when single-use plastic can remove barriers for people with disabilities.

We must also consider how we facilitate this in a way which respects both the right to access and the right to privacy.

Placcess is useful because it provides a simple public facing phrase to encapsulate the broader rights-based narrative. It can be accompanied by a symbol, displayed on stickers in bars, discretely alerting people with disabilities to the availability of plastic straws.

A sticker or a digital version for debit cards and digital wallets would allow people with disabilities to signal their need for a plastic straw without having to ask or explain.

The use of symbols in the service industry is not new – see for example the Challenge 25 logo which assists with conversation and restrictions around age restricted products.

A traffic light system for Placcess

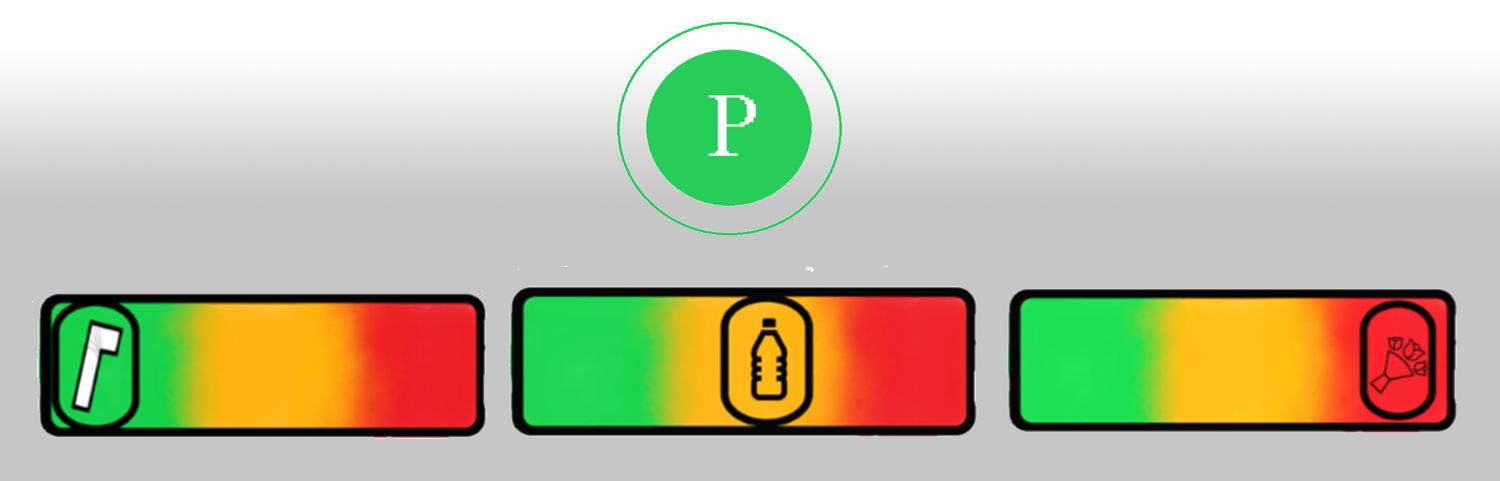

An awareness campaign for Placcess could be created along the lines of a traffic light system. The traffic light system has the benefit of being easy for customers of all ages to understand and is familiar, from nutritional labelling, in the UK. A traffic light system related to the ecological impact of food production has also been explored to assist consumer choice.

- Plastics that are essential to access and inclusion would be labelled as green and carry the Placcess logo. This group would include plastics used in medical packaging, straws, other products such as pre-cut produce (which can be vital for people who find it difficult to cut up fruit or vegetables), and incontinence products.

- Amber plastics would be those that people should look to avoid where possible. They would include things like plastic drinks bottles and toiletry packaging.

- Red plastics would be non-essential, plastics to avoid, for example, plastic-lidded coffee cups, fruit and vegetables packaging, plastic multipack wrapping and flowers, to name a few.

How a traffic light system and information symbol could work for plastic access.

This transitional approach to plastic reduction supports and emphasises a collaborative rather than punitive narrative.

Eventually, the Placcess symbol could be expanded to incorporate a swaps scanner like that used by the NHS initiative ‘Change4life’, helping consumers to identify swaps within a comparable price bracket.

The takeaway – people with disabilities care about plastic pollution, and ‘Placcess’ could help

People with disabilities care about the environment and want to help. However, their choices are limited.

We must work together with manufacturers and other stakeholders to widen these choices and to maintain and advance the equality of people with disabilities.

We need to talk about Placcess.

Acknowledgements

These ideas were first presented by Dr Pearson at a Keele University Institute for Sustainable Futures webinar on the 7th of December 2023. She is currently drafting an article based on the ideas in this blog which she will submit to the Journal of Environmental Law. Dr Pearson would like to thank her colleagues at Keele University for their comments on a draft of this blog, and her Access to Work support worker Elleanor Cornes, for her assistance with illustrations based on her instructions. Dr Pearson chooses to use person first language around disability based on her lived experience.

Guest authors work with us to share their personal experiences and perspectives, but views in guest articles aren’t necessarily those of Greenpeace.